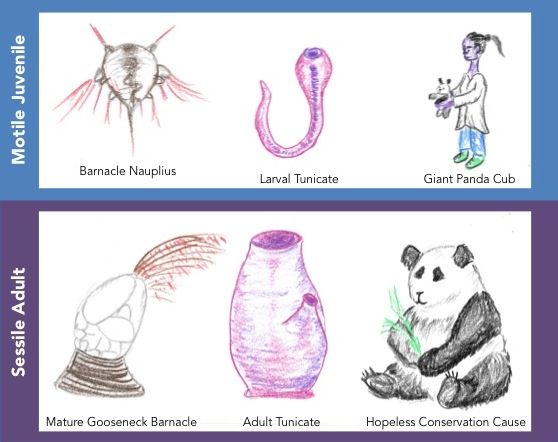

Life is a motile phenomenon. Even those wee beasties that we usually observe being sessile–bivalves, corals, sponges–spend at least one stage of their life adrift, however briefly.* And most animals spend their entire lives in motion.

Many movements are the quotidian practicalities of staying alive: foraging and fleeing, courtship and copulation, and so on. Other movements follow seasonal rhythms: wildebeest chasing rains, the great migrations of birds, the disappearance of catadromous eels to their surreptitious spawning waters.

Of all the sundry (and sometimes arbitrary) classifications of movement, dispersal holds a strange fascination for me. So much so that I hope to pivot from the study of recruitment (central to my Master’s thesis) to investigating patterns of dispersal for my doctorate.

The definition of dispersal is forthright: it is the movement of an organism from its birthplace to wherever it ends up breeding. The simplicity of this definition belies a complex and wondrous biological phenomenon, one that feeds into major concepts of population biology like gene flow, connectivity, distribution, colonization, and extinction.

But dispersal is perilous: an organism adrift can cross paths with harsh conditions, unexpected predators, and environs to which it is not adapted. There is no guarantee that the disperser will fall on fertile soil–it may wind up withering on rocks bereft of sustenance and opportunity.

Das Gleichnis vom Sämann, by Herrad von Lansberg. Uploaded via Wikimedia Commons.

Why bother dispersing at all? If we are raised successfully in a given area, doesn’t it stand to reason that our niche is most likely found close to our birthplace? What are the rewards of leaving home? What are the costs of staying?

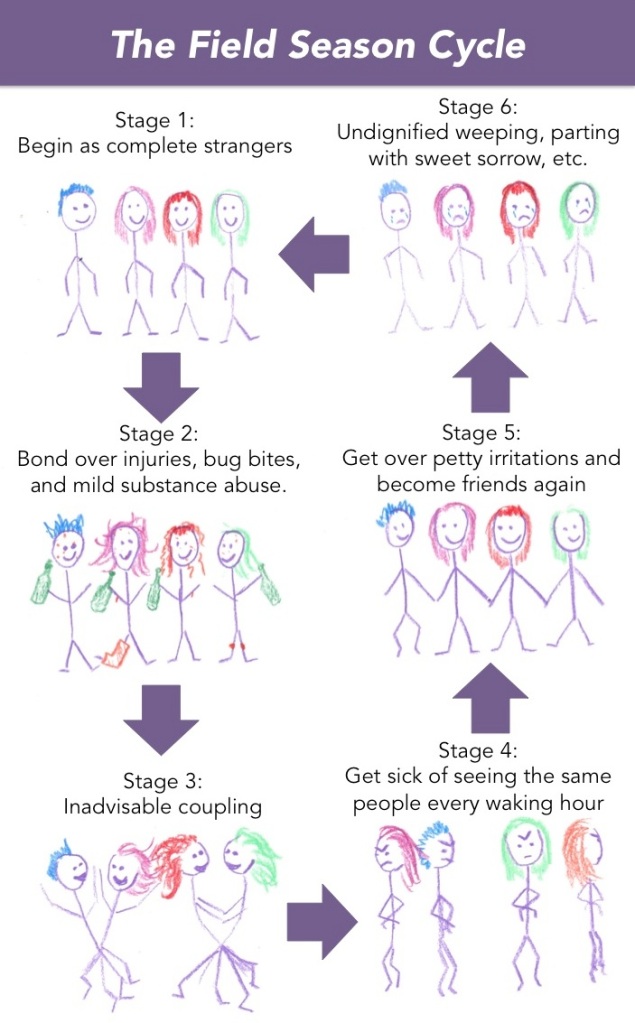

Even more than most academics, ecologists are creatures of profound wanderlust. In late adolescence, something calls from beyond the familiar streets of our homes and quaint college towns.

Away we go, chasing research questions across unsuspecting horizons. We live in cramped quarters with strangers that become friends and sometimes lovers.** We unconsciously create these little tribes feel like family until the project ends, the degree is finished, or the grant money runs out. Then we disperse again, parting with confoundingly sweet sorrow.

The adventure always wins out over the heartbreak. Perhaps the it wouldn’t really be an adventure without a little heartbreak. But again, I ask: what would it cost us to stay?

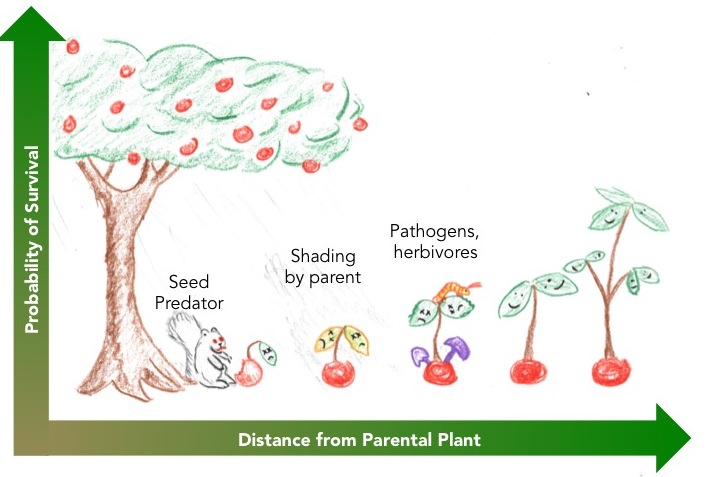

Baby plants on walkabout.

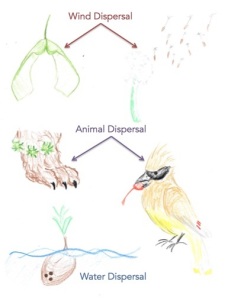

Plants provide some insight. They’ve devised countless strategies to send their offspring farther afield: sails of every shape and size to catch the wind, waterproof boats bobbing across wide waters, velcro cocklebur curls that hitchhike on fur and shoelace alike. So what happens to those apples that fail to fall far from the tree?

Turns out, the hazards of a seed landing too close to its parent are legion. The parent plant will be every seed predator’s favorite place to search for its next meal [1]. Even if a seed doesn’t get eaten, the newly sprouted seedling may have to compete with its parent for resources [2], and is subject to all the pathogens, parasites, and herbivores that rain down from above [3]. Clearly there is a strong selective benefit to dispersing under such conditions.

Perhaps our dispersals serve a similar end. Maybe we’re fleeing the hazards and vices that permeate our homes: the complacency that comes with comfort, personal stagnation in the absence of challenge, cozily toxic codependencies shared with family and friends.

Then again, we are not plants (even I can only stretch a metaphor so far). Perhaps I’d be better served seeking explanation within the same kingdom…

A great deal of research on dispersal in animals focuses on inbreeding avoidance, as the consequences of concentrating deleterious alleles over generations is–if not fatal–not very pretty [4]. Theory suggests that if an organism travels far enough, it will encounter mates genetically unrelated to it, with which it can produce suitably heterozygous offspring.

As an extra safeguard, patterns of dispersal are often sexually asymmetric (one sex demonstrating a propensity for hitting the road, while the other remains philopatric). Interestingly, the bias towards male or female dispersal varies greatly between and within taxonomic groups, and there has been plenty of hypothesizing as to how life history and social structure influence these patters [5, 6].

Examples of male and female sex-biased dispersal in 4 mammal orders. All images from Wikimedia Commons. (a) Spotted Hyena, (b) African Wild Dog, (c) Yellow Baboon, (d) Chimpanzee, (e) Common Shrew, (f) White-toothed Shrew, (g) Bechstein’s Bat, (h) White-lined Bat

It’s not clear whether or not humans have sex-biased dispersal; cultural practices of inheritance and nomadism strongly influence sex-specific patterns of movement. However, looking at the gender gap in post-secondary study-abroad programs, I’d hazard the guess that there might be some bias towards female dispersal in our species.***

That being said, I doubt that the average ecologist’s dispersal is merely a quest for outbreeding opportunities. Frequently, we leave behind partners in the pursuit of our science. Under the best of circumstances, our partings are amicable, tender, and affectionate. We allot ourselves a week to mope listening to sad music, and then carry on as though the loss weighs nothing.

Of course, there are intellectual rewards for being willingly untethered. Would Wallace and Darwin have every puzzled out evolution had they not witnessed geographic patterns of adaptive radiation firsthand? Would MacArthur and Wilson have put together the Theory of Island Biogeography without the visiting dozens of archipelagos?

I suppose we never know what patterns and mysteries will catch interest when we wander into the unfamiliar. Alternatively, we never know what discoveries we miss when we don’t stay put.

Ultimately, I don’t know whether there’s one or hundred reasons why we disperse, or if the rewards of dispersal will ever pan out. All I know is that, even with the excitement another day in the tropics will bring tomorrow, its the panoply of a hundred unfamiliar birds, blossoms and beetles beyond counting…tonight, a piece of my heart is aches for a city on a river two thousand miles away. A city full of friends that feel like family, a city with a thousand memories of love.

Somewhere that, in the moments I forget myself, I call home.

FOOTNOTES

*Maybe except for giant pandas. Those things are genuinely useless, and I’m pretty certain even the babies are lugged around by hovercraft conservationists.

**Great/terrible example of that here.

***Leastways, it’s a less obnoxious and condescending explanation than “Boys grow up slower than girls.” We do, but I don’t think that has anything to do with the pursuit of international study.

CITATIONS

1. DH Janzen. 1971. Seed predation by animals. Ann Rev Ec & Sys 2: 465-492.

2. R Nathan & HC Muller-Landau. 2000. Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment. TREE 15(7): 278-285.

3. CK Augspurger & CK Kelly. 1984. Pathogen mortality of tropical tree seedlings: experimental studies of the effects of dispersal distance, seedling density, and light conditions. Oecologia 61: 211-217.

4. FC Ceballos & G Álvarez. 2013. Roayl dynasties as human inbreeding laboratories: the Habsburgs. Heredity 111: 114-121.

5. PJ Greenwood. 1980. Mating systems, philopatry and dispersal in birds and mammals. Animal Behaviour 28(4): 1140-1162.

6. KE Mabry, EL Shelley, KE Davis, DT Blumstein, & DH Van Vuren. 2013. Social mating system and sex-biased dispersal in mammals and birds: a phylogenetic analysis. PLoS ONE 8(3): e57980.